NORA: How non-operating room anesthesia is evolving in our healthcare system

An official podcast of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, this episode of Central Line offers an in-depth exploration of non-operating room anesthesia, or NORA. Drs. Adam Striker and Basem Abdelmalak discuss procedures moving out of the OR, considerations for ensuring safety while realizing efficiencies, outcomes data, trends in NORA, and more. This episode is original programming from the American Society of Anesthesiologists and was sponsored by GE HealthCare. Recorded in May, 2023.

Show Notes

Transcript

Speakers

Our conversation focuses on the expanding use of NORA (non-operating room anesthesia) within our healthcare system. As hospitals seek to ease the burden placed on their perioperative resources, they turn to surgical and procedural needs being met outside of the traditional operating room setting. However, questions remain on how to select the right cases and optimize this non-traditional environment. In this interview, we:

- review existing data on safety outcomes, quality, and risk management within NORA

- review current trends on pre-procedure preparation

- discuss best practices for patient- and procedure-specific anesthesia technique and monitoring, including complications management and post-procedure considerations.

Welcome to ASA Central line, the official podcast series of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, edited by Doctor Adam Striker.

Adam Striker: Welcome back. This is Central Line and I'm Doctor Adam Striker, your host and editor. Today's topic is non-operating room anesthesia, or as is commonly known, N-O-R-A or NORA. We know that hospitals face great burdens on perioperative resources. In one way, they are responding to them by shifting some surgical and procedural needs outside of the operating room.

NORA cases are increasingly accounting for a larger percentage of anesthetics administered in the United States, and to help us think through how this is and how it should be working, I'm joined by Doctor Basem Abdelmalak, professor of anesthesiology at the Cleveland Clinic. Doctor Abdelmalak, thank you for joining us.

Basem Abdelmalak: Hi, Adam. Great to be with you and thank you for having me.

Adam Striker: And just for our listeners, this episode is sponsored by GE HealthCare, although neither me nor Doctor Abdelmalak have been compensated for this discussion and this discussion has been independently developed. Let's start, as we often do with the get-to-know-you question. Dr. Abdelmalak, why don't you tell our listeners a little bit about yourself and your experience with NORA.

Basem Abdelmalak: Absolutely. I practice at the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland. OH, I also served as the President for the Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia (SAMBA) in 2019-2020, during the COVID pandemic. I do a lot of writing and publication speaking on this topic that's near and dear to my heart. My involvement with NORA started with my involvement in establishing the state-of-the-art bronchoscopy suite outside of the operating room, hence the name NORA. Where we provide a whole host of advanced diagnostic bronchoscopy as well as therapeutic bronchoscopy. This has been functioning since, I would say 2010, has been around for 13 years or so, about 3 operating rooms that are fully equipped as a bronchoscopy suite and a hybrid operating room model with recovery room space attached to it to provide pre and post procedural services. I also provide anesthesia services at all other NORA locations around the hospital. As you know, SAMBA is involved in, and focus on all ambulatory anesthesiology services with all sorts of shapes including, but aren’t limited to, our patient anesthesia which was done in the hospital, or the freestanding ASC, and non-operating room anesthesia as well as open space anesthesia.

So, with that, I'm happy to answer some of the questions that you might have.

Adam Striker: Well, one of the biggest questions that we're going to tackle is how is it to administer anesthesia outside of the operating room, and that it oftentimes involves doing more with less. But before we get to that, I think it might be helpful to sort of lay out what we're talking about. I think many of our listeners are probably familiar with NORA, but in case there are those out there that aren't, let's talk about what settings we're talking about and why anesthetic care has evolved into those settings outside the operating room.

Basem Abdelmalak: Great questions. NORA refers to providing anesthesia outside the main operating room, but within a given hospital, and that includes many areas like gastroenterology and advent urology, bronchoscopy suite, cardiac cath lab, EP lab, MRI, nuclear medicine, you name it. And the list is growing by the month. It is also now providing anesthesia services for procedures in ICUs, pain management procedure rooms and such.

So, these are all the locations where we'll provide the anesthesia outside of the operating room. The old term, if you remember, used to be called remote anesthesia. ‘Remote’ kind of carries some negative feelings attached to it, so hence the name NORA kind of caught on, and people start using that term now to describe all services provided out of the operating room. So, there are some folks who would like to consider any other service outside the main pavilion operating room. Like freestanding ASCs or office-based anesthesia are part of the NORA services.

However, I believe that that would give this service to all these different services. It's better to focus on one item at a time and try to describe the characteristics and concerns and issues, and how we can do better in those patients. For example, the standards and the way we provide services in office-based anesthesia is much different than the ambulatory surgery center, where these tenders are different, the anesthesia machine is different, the facilities are different, the personnel are different and so forth. Even patient selection, the one you accept provide service for an office-based anesthesia is not the same as when you provide service for ASC or non-operating room anesthesia which is a NORA location within a hospital. And as you know, the freestanding it sees in our office-based anesthesia services, but totally 100% outpatient. However, if you look at NORA, it's mostly outpatient but 70%.

But we provide a good number of cases, about 30% or so for in patients who are higher acuity are very sick, and we still provide great care for them in those areas, so issues are different, and concerns are different and should be addressed separately.

Adam Striker: I'm sure there's multiple factors involved in the shift out of the operating room over the years for anesthesiologists. Just briefly, do you mind telling our listeners a little bit about those factors, what has happened over the last number of years to account for the shift, whether it's economics, logistics, differences in catering to different patient populations or other physician’s needs? Let's just touch on that briefly just to lay some groundwork.

Basem Abdelmalak: Sure, you're absolutely correct, it's multifactorial. There have been new advances in the procedures, so many of them now not requiring the full capabilities of the operating room and some of them require complex and immobile technology that are fixed into those NORA locations. Also, higher risk patients as the population ages and who are not considered candidate for surgeries in the past, now have an option, now have a minimally invasive procedure that can be done safely in NORA. And as you alluded to, economic trends that push for more outpatient versus inpatient services. So, all that has led to the movement towards not allocation. Also, but we cannot deny that if an area focuses on certain line of service or certain procedures and they do it day in and day out all the time. There is some value into that, where it would improve outcomes and help with efficiency as well. So, it's multi-factorial. It tells you we are moving to NORA.

Adam Striker: Okay, well, a few minutes ago we did mention that operating in a NORA environment oftentimes is doing more with less, as far as the anesthesiologist is concerned. So, let's dive into that a little bit, but let's start with talking about patient safety. Do you mind outlining what are some key points or aspects of performing anesthesia in the NORA environment that you feel anesthesiologists need to know as it pertains to performing an anesthetic safely?

Basem Abdelmalak: Absolutely, you touched on a very important point which is a hot topic. There are many of the anesthesiology team members who do not consider NORA as a desired assignment. Unfortunately, concerns are undesired. Some of the reason is that they are concerned for patient safety, because many of us feel like we do not have what we need, what it takes to provide the safest possible care there due to the many paths. Like, for example, if your retrofit anesthesia services in an area that's originally designed for procedural sedation or procedure under local anesthesia, they are not equipped, or they were not planning on having anesthesia service there. Now you are trying to retrofit anesthesia machine and anesthesia supplies and medications and equipment and so forth in there and you may miss one, you miss two and you don't have a way to communicate with your colleagues and such.

So, it becomes an issue when we don't feel that we have like fixable by service, but that can be easily overcome by proper planning. So, as you interpret an area, make sure you have a list, and that you have the current ASA statement on NORA in order to give a list of what kind of equipment that we need to have in there. And also, if you hear of a plan of building or establishing a new location, we got to be involved at the beginning of the blueprint stage, where we can decide on the space and the size of the area, how much we're going to need for our equipment, supplies and machines and electric outlets and lighting and so forth. So, we need to have what we need to be able to provide that kind of service.

Also, minor things, even like electrical outlets or adequate lighting or ability to access the patients, all these are safety features and, most importantly, our mirrors. The same level of monitoring, the same standards that we use the same essay standard model should be also used in non-operating room anesthesia and as we plan to provide services there, we should pay attention to a lot of other details, like patient selection, who should we serve there, and how can we provide that service safely. Other side items, like do we have access to difficult area management equipment? We should have that available.

Looking at what kind of policies in this area that they're utilizing, and can we move this tender up to what we have in our operating room? Code response, should we arrange for case of situation where we have a code, do we have a two-way communication to call for help or tech support? Or can we call for the rapid response team within the hospital?

So, there are many issues that we can address that would help us feel more comfortable and also provide what the means and what it takes to provide safe care in those locations.

Adam Striker: Well, this is always the case with the depends on the anesthesiologists. We're asked to do things in more and more efficient manners, and none of us wants to compromise safety. And as it pertains to NORA, how do we navigate all the items you mentioned, along with the demands for increased efficiencies, where we don't want to compromise safety in any way? I don't think anybody wants us to. But, as experts in patient safety and in the hyperacute delivery of medicine, we know that those realities exist. Talk a little bit about what are things we can do to maybe navigate those roadblocks.

Basem Abdelmalak: Oh, absolutely. Start from the beginning, from the start. If we're building a new area, we should try to build it as close to the operating room as possible, if not within the operating room pavilion. That would eliminate a lot of issues that we're talking about in terms of efficiencies and there's also safety as available, additional personnel that can help in case of emergencies that will be there. If that's not feasible and we're building multiple suites, it's better to have them all located in one area, one big floor, for example, one big clothing. So, this way we have very close proximity to each other where we can have a better ability to provide and staff those areas with personnel and having available additional hands to help in in emergencies as well.

Also consider opportunities for system-based triage. What kind of patients we need to get there? So as when you are putting a patient who is requiring a whole lot of work to get the case started, that is because there are deficiencies in that area, the scheduling is a huge piece of that. I mean, using block time was thought to be very, very helpful, but it is recommended to use the whole day block time versus partial day block time that has been shown to help. I will try to minimize the under- over- utilization of the block time that has a lot of economic disadvantages attached to all that.

Also, it would be helpful to incorporate NORA scheduling within the same scheduling frame that we use in the main hospital operating room. This way, the anesthesiologist in charge will be able to see what's happening in all locations at the same time, we're able to assign proper personnel to different areas, as you see, as the day goes. We need to work with our colleagues in those areas, we need to understand how we functional schedule our personnel and to what you probably see that your hospital, Adam, that they schedule sedation cases, or local anesthesia cases in between anesthesia cases. That's not appropriate, and that would be detrimental to efficiencies in providing services in those areas as well. And what kind of case, what kind of patients scheduled in the more complex patient probably should be done early in the day versus the contrary to have added the personnel and opportunities at the care of those cases versus one of these. So, there are many ways and many opportunities that we can do to improve the scheduling.

The main thing, and I cannot stress that enough, is the geographic footprint of these locations in the hospital. The closer we get them all together in one area close to the main operating room, the better it is for efficiency and scheduling and so forth and that should help us be able to provide that service efficiently and also economically. But we have to realize that oftentimes with the best effort, sometimes providing safe care and safe staffing of those areas, we might end up having their professional fees for anesthesiology services may not be adequate to cover the cost of providing safe cares. In those situations, we have added that to the revised language and the documents are being considered right now to replace the NORA statements to consider having the institutional financial support for those conceptions. As you know, institutions get additional revenues from facility fees and technical fees and such and they should consider contributing to the cost of providing safe anesthesiology care in this year.

Adam Striker: Well, I do want to talk about that statement, but before we get to that, you had mentioned earlier that oftentimes NORA assignments are not perceived to be good or plum assignments, and the reason for that is because of safety issues. Is there data to show that these environments are indeed less safe or is that really just a perception, not reality?

Basem Abdelmalak: No, there are many outcomes’ data out there. I mean, for example, data from 12 million patients in the NICORE database, which is a national anesthesia clinical outcome registry within the Anesthesia Quality Institute at the ASA looked at those patients, and they found that as we all know that NORA patients are older and we use Mac anesthesia more commonly than other modes or other forms of anesthesia and areas. One of the main findings in that study that showed that while the overall mortality in NORA is less than the operating room, 0.2% versus 0.4%, but if you parcel out cardiology and interventional radiology areas, those two areas had higher mortality than the main operating room, which may reflect the acuity or the high risk patients being taking care of in those areas or maybe the more invasive procedures that are being done there.

But more importantly, you also identified that the wrong patient or side procedures were higher in NORA than in the main operating room. And if you look at the close claim trials, it shows some very interesting data there. They found that respiratory events were higher in NORA than in the main operating room, and about 50% or so of them are preventable by better margin. And that data actually did not improve in the most recent close claim trial. One thing they identified is that the mortality claims or the claims in the non-operating room anesthesia had higher death and also had higher payout as well. So, these are real concerns. I mean, overall, the numbers are fortunately low, but as you know one is way too many when it comes to complications like that. And the fact that many of these events are preventable with better monitoring, it tells me that there's a lot more work to be done and we can do better.

Adam Striker: Certainly interesting and concerning numbers, but it seems that that would be an effective tool for heads of anesthesiology groups or organizations to go to the administrators and hospitals and say, hey, these are the facts and we need some support in making these environments a little safer, a little more efficient, a little more accessible, things like that. But that does seem like that would be one strong route to pursue.

Basem Abdelmalak: You're absolutely correct. I could not agree more. We have the data, and we know what's going on there and that's why I stressed earlier that we need to be sitting at table as we discussed different areas as we remodel, as we build, as we retrofit, as we start new service. We need to be there at the beginning to say well, this is what it takes to provide safe anesthesia care, these are kind of matters, we need this kind of equipment we need, and this is how we can provide safe service. How we can help you to provide the same care that you would like to provide with the highest level of safety that we can provide. We are leaders in patient safety, we are not to be so for decades, and we have been dealing with many, many safety initiatives in our own hospital around the country and in, in medicine in general. And this is part of this one area where we can actually show evidence that we can do that.

Adam Striker: Well, I have some more questions for you, including circling back to the updated ASA statement on NORA. So, please stay with me through a short break, we'll Be right back.

Alex Arriaga: Hi, this is Doctor Alex Arriaga with the ASA Patient Safety editorial board. Perioperative critical event debriefings are important for patient safety and the provider experience. Yet research suggests only a fraction of perioperative critical events are followed by any form of debriefing. The time shortly after a critical event presents a valuable opportunity to reflect, provide feedback, identify systems gaps, and lookout for each other's well-being. At a local policy level, there are crisis checklists, emergency manuals and other tools that can be a starting point to discuss events or debriefing may be most supported. Medical simulation may be a way to generate rare events and facilitate debriefing training in a safe space. Leadership support for a critical event debriefing can improve buy in. Efforts to improve critical event to briefing practices can benefit the individual team and overall health system.

For more information on patient safety, visit asahq.org/patientsafety22.

Adam Striker: Welcome back. Doctor Abdelmalak, you've been involved in updating the ASA statement on NORA, and you mentioned it earlier. Do you mind telling our listeners a little bit about that and the best practices it proposes?

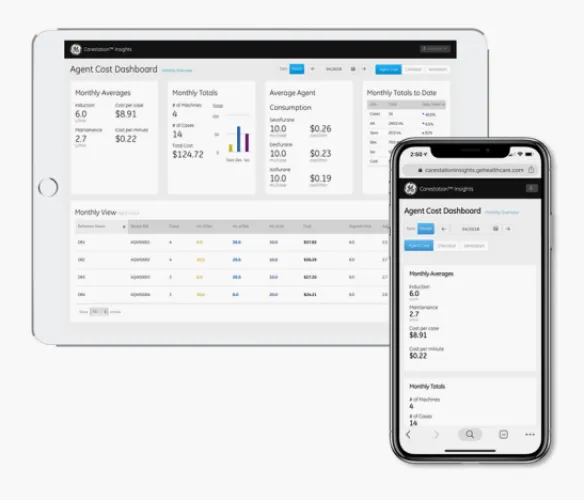

Basem Abdelmalak: Sure, I had the purpose of leading a group of national experts, including many ASC leaders and officers, to revise the ASA statement on NORA, the statement that we currently have has been around for many years and has helped us tremendously in establishing our NORA location, but with the new advances and expansions that NORA locations now account for about close to 50% of all what we do in anesthesiology services and all the new procedures and new locations and expansions, the group felt that it is time to revise that statement to match the current needs. So, the one-page document is now a four-page document, covers many items and is now being considered with the Committee on Procedure and Surgical anesthesia, but hopefully will be finalized and our readers will be able to read the full document when it gets posted on the ASA website very soon. We divided up the recommendations into many items, including facilities, design and equipment, environment of care, staffing and schedule optimizations, quality and safety, regulatory issues, supporting technology and IT systems, finance and budget, as well as materials management and steer processing. It's worth looking at when the document comes out, it would really help us as a starting point.

It doesn't tell the whole story, each one of us should adjust the items mentioned there and the recommendations to match their local needs and their community and their hospital and their health system. There are many ways of doing things, but this kind of gives us a framework to think about what's necessary, what's needed to provide the highest level of care, the safest level of care If you want to lower patient in those areas.

Adam Striker: Well, let's talk a little bit about new trends in NORA that you think our listeners should be aware of. Do you mind telling our listeners a little bit about what insights you have on newer trends regarding this area?

Basem Abdelmalak: Absolutely. First of all, it's expanding. If you look at the latest data that was published from 2014, was published in 2017 showing that NORA, it's close to 40% of what we do. If the trend continued as it was till now, I expect it to be around 50% of what we do. And also, the trends they're showing that its higher patient is increased as the years go by and also increased comorbidities as judged by their SA status. And more and more of them are becoming outpatient procedures, about 70% or so. So, there's increase in volume, there's increase in patient comorbidity is increasing in age and also increase invasiveness. I mean, there are more and more procedures being added to NORA allocation and NORA services. I can just give you one example. Many IR departments around the country started to now provide pulmonary thrombectomy for patients who admitted to our ICUs with PEs in the IR department. That's another service being done there. There are many new procedures as well being added to bronchoscopy. For example, now there's a robotic bronchoscopy being added and there are many other new advances in navigational bronchoscopy and diagnosing lung cancer. And there's even a new technology coming on to not just diagnose lung cancer, but treat lung cancer by ablation therapy and many other techniques. So, there are new technology, new procedures being added, and we need to stay abreast of what's happening in this location, what kind of service do you provide there.

Adam Striker: Well, let's talk a little bit about that. Anesthesiologists involved in areas where Proceduralists want to introduce a new procedure, whether it's something that hasn't been done before, whether it's increased acuity, what should the anesthesiologist do, what resources are there, what should be done beforehand?

Basem Abdelmalak: That is a great question. First, we need to understand more about the procedure. Let's have a conversation with the proceduralists that wants to add that procedure. Let's learn a little bit more about it. How is it going to be done, with what kind of equipment needed for that procedure? What kind of patient population will need or require this kind of procedure to see how we can optimize them and get them better? We can provide patient selection criteria or pre-op-evaluation and such for that. We can do literature search: anesthesiology literature as well as the proceduralist specific literature, to learn more about the procedures, see if any other colleagues are doing it around the country. And there are many resources, for example, those coming to the ASA annual meeting. I had the privilege of leading the ambulatory track for the last three years. And I know this year we're having a lot of NORA-focused presentations and talks and such, and also certified ambulatory and anesthesia annual meeting and many sessions focused on NORA. Loads of resources available there for the ASA website: asahq.org or SAMBA website sambahq.org. And also, many publications from our colleagues, and we have published some showing how to address new procedures.

One item that would I encourage folks to do is to do a dry run before they start any new procedure. Meaning like have a calendar room or something like that and talk about how this procedure is going to go, anticipate complications, and see how the teams got to respond to it. Assign roles when something like that may happen, then you know who's going to respond to what, who's going to call for her, who's going to grab which equipment, who's going to do which intervention. And then also make sure that you have the equipment and the resources needed to address these potential complications from that procedure as well. Now we have done that successfully when we introduced a new procedure, for example robotic bronchoscopy, using the robot with a mannequin. And we looked at how that robot gets attached to the airway, the endotracheal tube, and if complications happen, how we're going to gain access to the airway one more time, who's going to be disconnecting the machine from the airway, and who's going to be moving the equipment out of the way for the anesthesiologists and pulmonologist to gain access and intervene to help with whatever potential complications like pneumothorax or bleeding and such an airway that we can help with.

So, these are some strategies that people can use to help us start and to introduce a new procedure in in an area in a safe manner. And sure enough, once we did the dry run and got everybody assigned to roles and we'll make sure that we have the equipment we need to address potential complications, we have been able to provide the service safely for a long time now.

Adam Striker: Well, before I let you go, let's talk a little bit about the role of anesthesiologists. As we've talked, you've certainly laid out a great case for why it is important that anesthesiologists play a key role in developing and driving future policy measures surrounding NORA practice. Just talk to our listeners a little bit about what kinds of policies they should expect to be involved in, they should maybe look to be involved in and maybe what are some pitfalls that we should be aware of when engaging in that development.

Basem Abdelmalak: Oh, absolutely. I mean we should look at NORA as if it's an operating room and if you provide service there, it's prudent to follow the same safety practices that we follow in the operating room. Starting from simple things like patient identification and site identification. As I mentioned earlier, wrong site surgery has been found to be higher in NORA than an operating room, and we have gained great skills and insights on how to prevent that in an operating room. We can help our colleagues in those areas to prevent that as well. Patients coming for anesthesia should have also the same systems we have in an operating room, for example, we need to write and be responsible for some pauses in those areas, like NPO guidelines, and also recovery criteria there. How, when are we going to discharge this patient? How are we going to recover them in those areas and training the area nurses? How to recover those patients? How to manage AICDs and peacemakers in that area? And more importantly, patient selection and pre-op evaluation. When and where is going to be done? Is it needed or not? And what kind of items you need to focus on? What specifics for that area, for that patient population being served or that procedure that being done in that area.

We have been again the safety leaders around the country, around the hospitals and we need to continue with our leadership role in those areas. While writing policies is not one of the most desired activities for anesthesiologists, it is very important. And because these are the ones that we're going to end up having to follow. And who would be better to write policies related to anesthesiology practice than the anesthesiologist in charge of that area? And I encourage folks to have leadership assignments in that area from anesthesiology from the procedural side, from nursing side, so those leaders can communicate regularly and frequently to address any issues that may arise. This way we have a point of contact to reach out to when issues arise and resolve it quickly and that would result in better satisfaction of the teams and better safe care for our patient.

Adam Striker: Well, Doctor Abdelmalak, I really enjoyed the conversation today. Thank you for providing such a nice overview on really what it is such a key component for almost every anesthesiologist, no matter what area you might be practicing in the idea of practicing and non-operating room anesthesia. So, thank you for joining us today.

Basem Abdelmalak: Thank you for having me. I enjoyed it as well.

Adam Striker: And to our listeners, thank you very much for tuning in again to this episode of Central Line. Please tune in again next time. Take care.

Stay ahead of the latest practice and quality advice with ASA anesthesia standards and guidelines freely available to keep you up to date. Browse now at asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines. Subscribe to Central Line today wherever you get your podcasts or visit asahq.org/podcasts for more.

Dr. Adam Striker, MD

Adam Striker, MD, FASA, is currently Chair of the ASA Committee on Communications, and is the series editor for ASA’s Central Line podcast series. He is an Associate Professor and serves as staff anesthesiologist in the Division of Cardiac Anesthesia at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and in the Division of Pediatric Anesthesia at Kentucky Children’s Hospital as part of the Joint Congenital Heart Care Program. He received his undergraduate degree in engineering from Purdue University and his medical degree from Indiana University. He completed his pediatric anesthesiology fellowship at Northwestern University.

Dr. Basem Abdelmalak

Dr. Basem Abdelmalak is a professor of anesthesiology at Cleveland Clinic. He leads NORA services for bronchoscopy and is the quality improvement officer and director of the anesthesiology oversight for procedural sedation. He also performs the therapeutic whole lung lavage procedure. His clinical interests include anesthesia for ENT and difficult airway management. He recently served as a member of the ASA task force on the 2022 ASA practice guidelines for the management of the difficult airway. His research interest is focused on perioperative diabetes and hyperglycemia management.

Dr. Abdelmalak served as the past president of the Society for Head and Neck Anesthesia (SHANA), the Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia (SAMBA) and the Ohio Society of Anesthesiologists and currently a member of the ASA board of directors. He has received numerous awards, including safety champion by the Cleveland Clinic Quality Institute and co-edited two textbooks titled Anesthesia for Otolaryngologic Surgery and Clinical Airway Management