Stable chest pain is a common complaint seen in cardiologists' offices, but the proportion of patients who will have an obstructive coronary artery stenosis is "relatively low" at about 10 percent, according to recently released chest pain guidelines from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and other societies.1 The way diagnostic tests are currently deployed results in many patients (a percentage as high as 50 to 60 percent) having normal findings on invasive angiography, and it's possible that initially relying on simpler, less-expensive evaluations, such as an exercise stress test, could be useful.

Choosing a Test for CAD Patients

In deciding how to evaluate a patient with CAD, physicians have several tests to choose from and must consider multiple factors, including:

- Patient features

- Local availability of tests and expertise

- Contraindications to a particular modality

- Cost

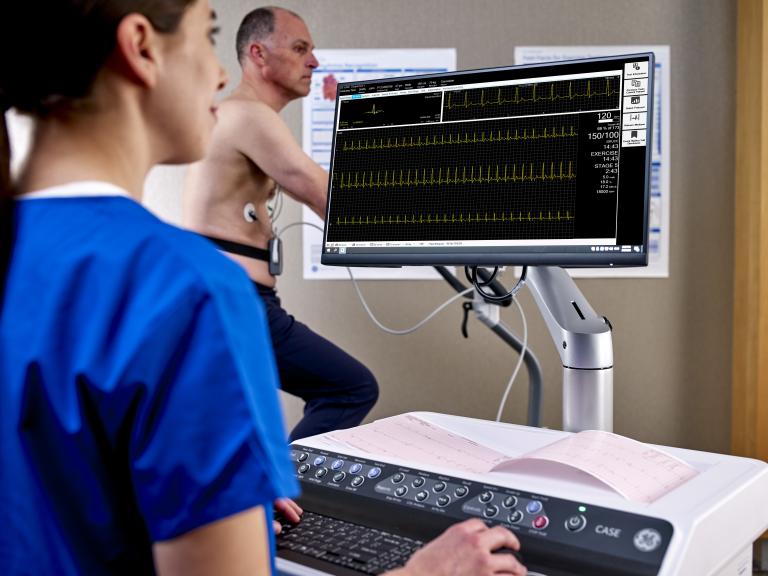

The authors of the chest pain guidelines point out that "A general concept regarding cost is that layered testing (ie, when a test is followed by more tests) leads to higher costs. To minimize the potential needs for downstream testing, clinicians should select the test that is most likely to answer a particular question." They add that studies have suggested that tiered testing strategies starting with exercise ECG have more favorable cost-effectiveness compared to other approaches. Exercise ECG is also one of the lowest-cost diagnostic tests, with the added benefit of no exposure to ionizing radiation as well as being completely noninvasive.

There is not universal agreement on how exercise stress tests should be used in the initial evaluation of CAD. The latest guidelines on chronic coronary syndromes from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC),2 for instance, recommend use of noninvasive functional imaging for myocardial ischemia or coronary CT angiography (CCTA) as the initial diagnostic test in symptomatic patients when the presence of obstructive CAD can't be excluded based on clinical factors alone. Patients are sent to the cath lab for invasive angiography when there is a high likelihood of an obstructive coronary artery stenosis, "severe symptoms refractory to medical therapy or typical angina at a low level of exercise, and clinical evaluation that indicates high event risk."

Exercise ECG is indicated, according to the ESC guidelines, "for the assessment of exercise tolerance, symptoms, arrhythmias, BP response, and event risk in selected patients," and it may be considered as an alternative for the diagnosis of CAD when noninvasive imaging isn't available.

How Guidelines View Exercise Stress Tests

In light of the debate over where exercise stress tests fit in with regard to evaluating patients with CAD, the new U.S. chest pain guidelines provide much-needed guidance for physicians. The first step should be a calculation of the pretest probability of obstructive coronary disease using newer models.

Generally, patients deemed to be at low risk according to this assessment can have testing deferred. However, it's reasonable, according to the guideline writers, to use CAC testing to exclude calcified plaque and identify patients who have low risks of obstructive CAD and future CV events. The writers also claim that exercise testing can be used without imaging as an initial test to either exclude myocardial ischemia or assess the functional capacity of a patient with an interpretable ECG.

Test choice becomes more involved in patients with intermediate-to-high pretest probability, a group with "modest" rates of obstructive CAD (10 to 20 percent). While CCTA is favored in patients younger than 65 who are not taking optimal preventive medications, stress testing "may be advantageous in those ≥ 65 years of age, because they have a higher likelihood of ischemia and obstructive CAD." Moreover, studies in recent years have indicated that patients being considered for elective angiography "may be safely triaged using CCTA or noninvasive stress testing."

For patients in the intermediate-to-high-risk category who have stable chest pain and no known coronary artery stenoses, the strongest recommendations are for use of CCTA and stress imaging, including stress echocardiography, PET/SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging.

The U.S. guidelines are more open to use of exercise ECG when it comes to index diagnostic testing, stating that it is a reasonable option in patients with interpretable ECGs and the ability to achieve maximal levels of exercise (at least 5 METs). Though diagnostic accuracy is lower with exercise ECG than with other modalities, "prognostication remains a useful goal," the authors say. They cite the WOMEN trial showing that exercise ECG was comparable to exercise SPECT MPI when it came to 2-year CAD event rates.3 In addition, how patients perform on a stress test has been shown to correlate with CAD event risk.

Stress imaging may be needed to improve the assessment of a patient's risk and guide clinical management when patients either can't exercise sufficiently or have ischemic signs on ECG. Patients with indications of marked ischemia may require additional anatomic or stress testing.

To learn more about the power of the ECG in today's clinical landscape, browse our Diagnostic ECG Clinical Insights Center.

What To Do After CAD Is Identified

The U.S. chest pain guidelines provide advice on selecting tests in patients with known CAD and stable chest pain despite optimized medical therapy. Stress PET/SPECT MPI, CMR, or echocardiography are recommended for diagnosing myocardial ischemia, projecting risks of future adverse outcomes, and guiding management.

Exercise treadmill testing "can be useful" for determining whether symptoms are related to angina, evaluating symptom severity and functional capacity, and guiding management decisions around use of additional medications, cardiac rehabilitation, or coronary revascularization, the authors say.

Whichever tests are used, the ultimate aim is to identify patients with obstructive coronary artery stenoses who will benefit from guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), as detailed in various guidelines on stable ischemic heart disease,4 cholesterol management,5 and primary prevention of CVD.6

"In patients with known CAD, clinicians should opt to intensify GDMT first, if there is an opportunity to do so, and defer testing," the guideline authors advise. "Although GDMT exists for obstructive CAD, there are no current guidelines that are specific to nonobstructive CAD. Thus, adhering to atherosclerotic CV prevention guidelines is recommended."

References:

1. Gulati M, Levy PD, Mukherjee D, et al. "2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines." Journal of the American College of Cardiology. October 2021. https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.053

2. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. "2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes: the task force for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)." European Heart Journal. August 2019;41(3):407–477. https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/41/3/407/5556137

3. Shaw LJ, Mieres JH, Hendel RH, et al. "Comparative effectiveness of exercise electrocardiography with or without myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography in women with suspected coronary artery disease: results from the What Is the Optimal Method for Ischemia Evaluation in Women (WOMEN) trial." Circulation. August 2011;124(11). https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circulationaha.111.029660

4. Fihn SD, Blankenship JC, Alexander KP, et al. "2014 ACC/AHA/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS focused updated of the guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease." Circulation. July 2014;130(19). https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/cir.0000000000000095

5. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. "2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol." Circulation. November 2018;139(25). https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625

6. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. "2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease." Circulation. March 2019;140(11). https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678