It was during ward rounds on the Cardiology service, when one of my attendings said very bluntly, "stenting causes myocardial infarctions, so never do an angiogram for coronary artery disease unless you absolutely have to." The words seemed odd at the time—if there is a blockage, shouldn't opening it up make the most sense? And don't Cardiologists love doing cardiac catherizations?

So, those words certainly made me pause. But since then, I have come to appreciate just how powerful those words were and have relied upon that mantra to make decisions about when to send patients for invasive angiography.

Too Many "Inappropriate" Angiograms

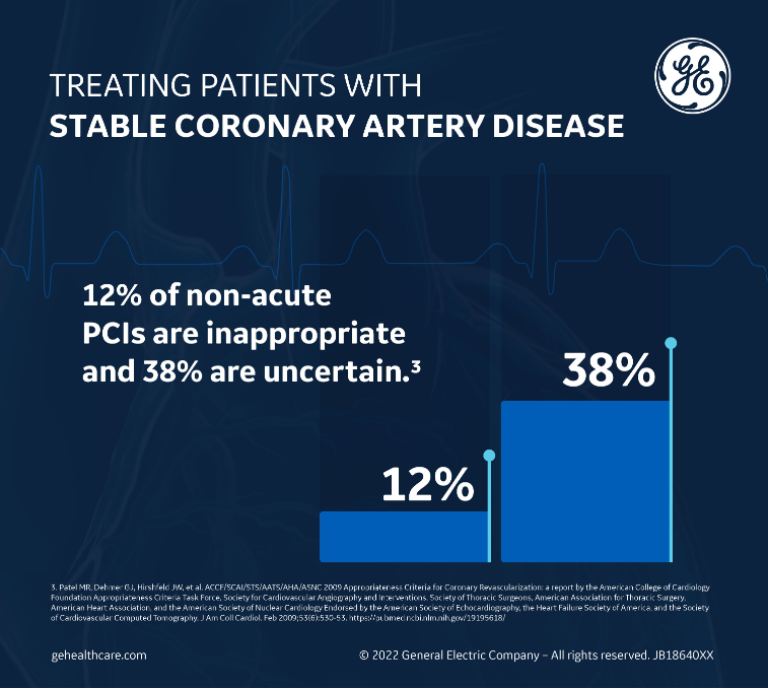

Heart disease is the number one killer of men and women in the United States and worldwide, so it should come as no surprise that expensive Cardiology procedures such as coronary angiograms are also often the biggest money-maker for hospitals, even though they come at a substantial expense to the healthcare system of $12 billion/year.1 In fact, a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association2 classified 12% of nonacute percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) as "inappropriate," with an additional being 38% classified as "uncertain" based on published appropriate use criteria.3

When you factor in that ~5% of coronary angiograms can be complicated by major bleeding, renal dysfunction, arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, or even death, this leads to an unacceptably high rate of complications for procedures that may not even have been appropriate to begin with.

Interestingly, nearly all of the acute PCIs performed were classified as "appropriate." When it comes to management with invasive modalities such as coronary angiograms, the critical decision point then appears to be the acuity and severity of the symptoms, and whether the patient falls into the acute coronary syndrome category or the stable CAD category. It seems our clinical decision-making is more intact with regard to acute coronary syndromes, but there is a high amount of variability between hospitals, health systems, and physicians when it comes to stable CAD management.

This is because when it comes to stable CAD treatment, the decision-making turns out to be a lot more nuanced and complex. The goals of revascularization in this disease state are to: (1) alleviate symptoms; or (2) reduce the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events such as death, heart failure, or myocardial infarction. And if you are not doing either, then revascularization may actually do more harm than good. Yet, as healthcare providers and as individuals under external financial and non-financial pressure from hospital systems our tendency is to do more rather than less.4

Noninvasive Tools for Diagnosing and Assessing CAD Patients

Although the pace and management of acute coronary syndrome and stable CAD conditions are very distinct, the tools we use to diagnose and assess our patients initially should always be the same. These basic noninvasive tools should always appropriately guide our hand toward or away from more invasive procedures, such as angiograms, which can carry substantial risk. These are the tools that allow us to practice our trade with expertise and skill.

Clinical History and Exam

The most fundamental of these tools is the clinical history and exam. When you actually listen to the patients and allow them to tell their story without interruptions, it will often guide your next diagnostic step in determining whether there is obstructive CAD present and, if so, what the next best strategy for management should be.

I clearly remember one of my young patients who, in textbook fashion, described to me a linear "tearing" pain that radiated to his back, started while he was hiking, and correlated with the onset of his chest pain. Listening to this patient's history prompted a STAT simple chest X-ray, which diagnosed his widened mediastinum and aortic dissection, saved him a risky trip to the catheterization lab or potentially dangerous stress testing, and directed him to the operating room emergently.

With respect to the diagnosis of suspected coronary atherosclerosis, the 2021 ACC/AHA Chest Pain Guidelines have now updated the definition of chest pain to mean more than just pain in the chest, including pain the shoulders, arms, neck, back, upper abdomen, or jaw.5 It also includes symptoms that patients may not always associate with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or angina, such as fatigue or nausea, especially in women. In fact, it is no longer recommended to use "atypical" as an adjective to describe chest pain not thought to originate from the heart. Instead, the term "noncardiac" chest pain is recommended.

Broadening the definition in this way and changing the terminology not only enables increased sensitivity for coronary atherosclerotic disease detection but also allows more focused additional diagnostic testing. For example, a "noncardiac" chest pain suggests that no further cardiac testing is indicated, while "atypical" chest pain suggests that the patient may have an atypical presentation and could still benefit from additional diagnostic CAD testing.

The Electrocardiogram: A Fundamental Tool

The next step in the evaluation of a patient with suspected ACS or CAD should always be the ECG, which is recommended by multiple expert medical societies and organizations, including the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association,6 and the European Society of Cardiology.7 In potential ACS situations, ideally the 12-lead ECG should be obtained within ≤10 minutes of presentation, with interpretation by an experienced physician.

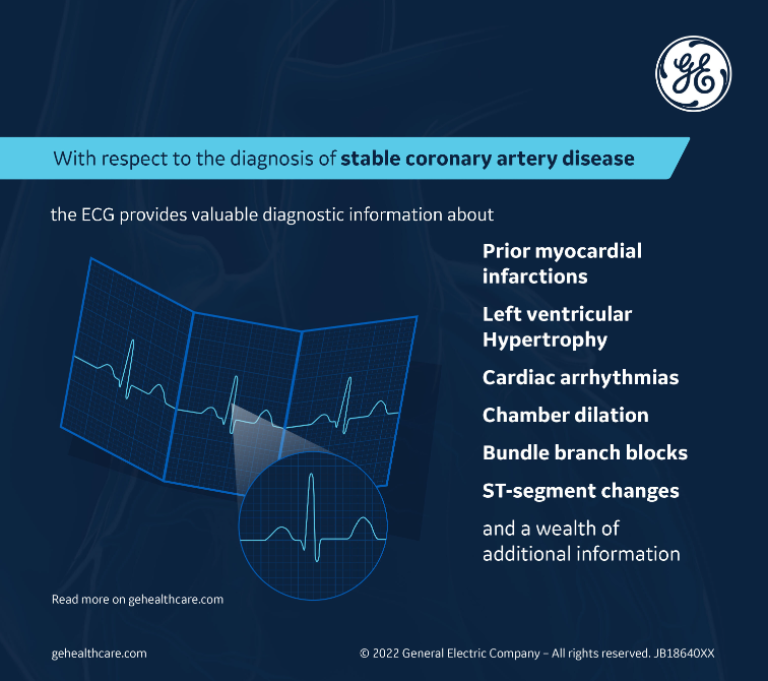

With respect to the diagnosis of stable CAD, the ECG also provides valuable diagnostic information about prior myocardial infarctions, left ventricular hypertrophy, cardiac arrhythmias, chamber dilation, bundle branch blocks, ST-segment changes, and a wealth of additional information that can steer the clinician's decision-making toward additional diagnostic testing, whether it be a stress test, an echocardiogram, or an ambulatory arrhythmia monitor.

In the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ECG can offer valuable diagnostic information about which patients may be suffering from long COVID-19. In these patients, the chest pain is likely not a result of coronary atherosclerosis but instead a manifestation of dysautonomia or perhaps myocardial inflammation from this virus that has receptors on the endothelium as well as the myocardium.

Noninvasive Diagnostic Testing Modalities: Cost-Effective and Guideline-Recommended

In the ER, after a high-sensitivity troponin has excluded ongoing active myocardial ischemia in a patient presenting with chest pain, the patient will likely benefit the most from additional cardiac imaging and testing if they had an intermediate or intermediate-high pretest probability of obstructive CAD, according to the 2021 ACC/AHA chest pain guidelines. Low-risk patients do not need urgent additional diagnostic testing.

With respect to patients with suspected stable CAD and intermediate pretest probability of obstructive CAD, current clinical practice and appropriateness guidelines recommend either exercise treadmill testing (ETT) or noninvasive cardiac imaging tests (such as stress echocardiography, myocardial perfusion scintigraphy, or coronary computed angiography) to diagnose, prognosticate, and make therapeutic decisions.

The use of cardiac imaging testing, which may offer slightly better sensitivity and specificity, is often the testing modality of choice for clinicians. However, a study published in Clinical Imaging concluded that initial ETT followed by imaging when ETT was equivocal proved to be more cost-effective than any strategy employing initial testing with imaging.8

Coronary calcium scoring (CAC), which has gained increased popularity, is also now able to diagnose CAD much earlier in asymptomatic patients. In these nonobstructive CAD patients, medical management with lipid-lowering therapy and aspirin, if appropriate, followed by noninvasive diagnostic tools to assess the severity of stenoses continue to be the most important management approaches. For patients with CAC > 1000, which is considered a CAD-disease equivalent, an angiogram is rarely indicated unless the noninvasive stress testing is abnormal.

Routine Revascularization in Stable CAD Does Not Improve Survival

The COURAGE trial, a randomized controlled trial in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2007, found that as an initial management strategy in patients with stable CAD, Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) did not improve cardiovascular outcomes, including death, MI, or other major cardiovascular events when added to optimal medical therapy.9 It was a game-changer. Hardly anyone expected this result, but it was entirely congruous with the guidance my attending had given me on rounds.

This article started the paradigm shift and was the first of many that made us realize that coronary stenoses may not always benefit from stenting and revascularization, and that medical management in selected lower-risk patients offered the same benefits without the risk of an invasive procedure.

In 2020, the ISCHEMIA trial—which studied patients with chronic CAD treated with an early invasive strategy (PCI or CABG) involving medical therapy vs. medical therapy alone—showed similar cardiac events and mortality. Peri-procedural MI was higher in the group that received PCI, but spontaneous MIs and angina were reduced with PCI. These results apply mostly to patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function. Special groups of consideration include patients with diabetes and advanced chronic kidney disease.

There are some patients who are likely to benefit from revascularization, with no controversy. These are patients with high-risk anatomy in which there is a survival benefit (left main disease or equivalent) or multivessel CAD, especially with a reduced left ventricular systolic function or a large area of potentially ischemic myocardium. It can also be considered for patients who are having activity-limiting symptoms despite maximal medical therapy, or patients looking to increase their activity level.

One of the reasons why the benefit of revascularization has been marginal in stable CAD is that we have become so good at medically managing disease through appropriate diagnosis, prevention, and risk factor management. The goals of medical management for stable CAD are the treatment of anginal symptoms (with beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and nitrated), initiation of disease-modifying therapies (statins, aspirin, other P2Y12 inhibitors), and risk factor management (anti-hypertensive, oral hypoglycemics), which can reduce disease progression and improve outcomes.

Shared Decision-Making

We have come a long way from the top-down decision-making that used to be the culture of medicine. When faced with a complex decision, such as revascularization for stable CAD, both the art and the science of medicine require that we involve our patient, their preferences, their lifestyle, and their choices in the decision on whether to offer revascularization.

The discussion, which should always occur before angiography, should involve an explanation of the diagnostic procedure as well as any potential interventions. During this discussion, it is critical to emphasize both the benefits of PCI, which may include less angina and a lower likelihood of another intervention in the first few years, as well as the risks of an invasive procedure and the potential for prolonged anti-platelet therapy.

Solutions

When we're faced with a situation where a patient presents with an acute coronary syndrome, we know what to do: The angiogram and revascularization of the culprit (and in some cases, even non-culprit lesions) are guideline-recommended and indicated. We are good at getting this right.

However, when we're faced with an average patient without any diabetes or chronic kidney disease who presents with stable coronary artery disease in the clinic, we must resist the urge to send the patient immediately for a diagnostic angiogram. In such situations, maximizing medical therapy and using noninvasive diagnostic modalities, such as the clinical history and exam, the ECG, and the judicious use of stress testing, can prove to be more cost-effective and offer more sophisticated and refined clinical decision-making with respect to the need for an angiogram and the appropriateness of revascularization.

Even if the patient is deemed appropriate for revascularization, having ancillary information from the ECG and echocardiogram can inform the decision about the best way to revascularize the patient (PCI or CABG) and can minimize the risk of peri-procedural complications.

REFERENCES

- Mahoney EM, Wang K, Arnold SV, et al. Cost-effectiveness of prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes and planned percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the trial to assess improvement in therapeutic outcomes by optimizing platelet inhibition with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction TRITON-TIMI 38. Circulation. Jan 2010;121(1):71-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20026770/

- Chan PS, Patel MR, Klein LW, et al. Appropriateness of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JAMA. 2011;306(1):53-6. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1104058

- Patel MR, Dehmer GJ, Hirshfeld JW, et al. ACCF/SCAI/STS/AATS/AHA/ASNC 2009 Appropriateness Criteria for Coronary Revascularization: a report by the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriateness Criteria Task Force, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, and the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology Endorsed by the American Society of Echocardiography, the Heart Failure Society of America, and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. Feb 2009;53(6):530-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19195618/

- Sternberg S, Dougherty G. Are Doctors Exposing Heart Patients to Unnecessary Cardiac Procedures? U.S. News & World Report. https://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2015/02/11/are-doctors-exposing-heart-patients-to-unnecessary-cardiac-procedures Accessed Nov 29, 2021.

- Gulati M, Levy P, Mukherjee D, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the evaluation and diagnosis of chest pain: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. Nov 2021;78(22):e187–e28. https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.053

- Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. Dec 2014;64(24):e139-e228. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25260718/

- Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet J, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).European Heart Journal. Jan 2016;37(3):267-315. https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/37/3/267/2466099

- Min JK, Gilmore A, Jones EC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic evaluation strategies for individuals with stable chest pain syndrome and suspected coronary artery disease. Clin Imaging. 2017;43:97-105. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5410386/

- Boden W, O'Rourke R, Teo K, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503-1516. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmoa070829